Why Walk Again post brain injury?

People who walk after BI live longer, live better, live healthier

What is an acquired brain injury?

A severe brain injury occurs when trauma to the brain produces a significant neurological injury resulting in physiologic changes to a person’s brain. Four types of injury may cause trauma to the brain:

Closed Head Injuries: Brain tissue impacts the inside of the skull. This can cause bleeding, bruising, tissue damage, specific neurochemical changes and increased intra-cranial pressure or fluid buildup.

Open Brain Injuries: Include penetrations, open fractures of the skull, entry of any foreign object into the brain, resulting in damage to the brain structure neurons.

Anoxic injuries: Lack or reduction of oxygen causes brain cells to die. Anoxic injuries can produce widespread effects throughout the brain.

Toxic injuries: Caused by exposure to certain toxic chemical agents, which can cross the blood-brain barrier and damage or kill brain cells.

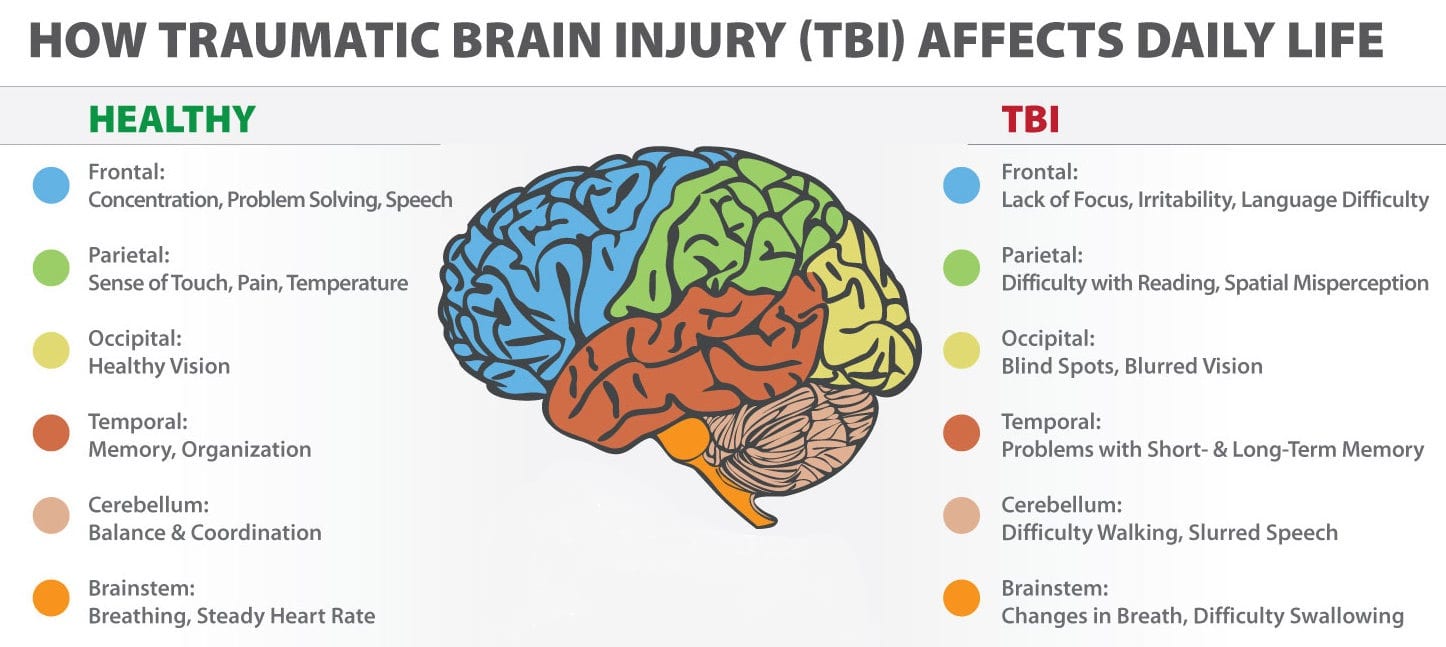

Individuals with traumatic brain injury (TBI) and other brain injuries often experience a complex blend of physical, sensory, cognitive and/or psychological challenges. A person with a severe brain injury will need to be hospitalized and may have long-term problems affecting things such as:

ThinkingMemoryLearningCoordination and balanceMovement and ambulation challengesSpeech, hearing or visionEmotions

Often, the devastating effects of a brain injury are not fully understood until after the patient has completed medical treatment in an ICU and has entered rehabilitation.

Long-term disability is a frequent sequel of severe brain injury and takes the form of persisting motor impairments that impact walking and autonomous movement. To improve environmental negotiation and basic care skills, independent gait is an essential therapy goal for BI patients.

For a brain injury survivor, learning to walk again should be a top priority.

Walking after a brain injury: recovery is possible

Most people who have had a significant brain injury will require long-term rehabilitation. They may need to relearn basic skills, such as walking or talking. The goal is to improve their abilities to perform daily activities.

Therapy usually begins in the hospital and continues at an inpatient rehabilitation unit, a residential treatment facility or through outpatient services. The type and duration of rehabilitation varies by individual, depending on the severity of the brain injury and what part of the brain was injured.

Ambulation is a crucial component to recovery and lifetime health. Movement keeps joints lubricated and stimulates the survivor’s brain, encouraging brain plasticity repair. Stronger muscles and bones provide the strength and balance the brain injury survivor needs to be active.

Physical therapy programs should be designed to help with mobility and relearning movement patterns, balance and how to stand and walk again. Brain injury survivors may need to go slowly.

Walking ability has important health implications, providing protective effects against secondary complications common after a brain injury, including musculoskeletal issues, systemic challenges, risk of falling, fractures, and experiencing another brain injury. Long-term complications associated with TBIs include Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease and post traumatic epilepsy.

While brain injury survivors learn at different rates, virtually all survivors can relearn. Even if someone has been primarily wheelchair or bed-bound for years, with little intervention, they can achieve significant results and greater quality of life with the proper program, and with proper equipment.

Many of our GHSII clients see consistent standing and walking progress in the months, years, or even life span of brain injury recovery. The brain has significant potential to do, adapt, and change, even years after injury.

Why is walking affected by brain injury?

People with traumatic brain injury (TBI) commonly report problems with balance. Between 30% and 65% of people with TBI suffer from dizziness and disequilibrium (lack of balance while sitting or standing) at some point in their recovery. Dizziness includes symptoms such as lightheadedness, vertigo, and imbalance.

The ability to maintain balance is determined by many factors, including physical strength and coordination, senses, and cognitive ability. Adjusting posture or taking a step to maintain balance before, during, and after movement is a complex process that is often affected after brain injury.

Physical therapy should work on body discoordination issues to improve the survivor’s walking and balance, with an exercise program tailored to meet their specific needs.

A patient’s balance may be shaky if the cerebellum is injured. Along with weakness and loss of balance, many brain injured patients experience sensory deficits.

Injury to the motor portion of the brain can also diminish muscle tone and control, another obstacle to walking. Muscles can lose the ability to contract altogether or, on the contrary, become overly contracted and too rigid to allow a simple walking motion.

How does a brain injury survivor learn to walk again?

A patient’s rehabilitation should start as soon as he or she is stable. Established guidelines, as well as a huge body of literature, insist that the earlier therapy is initiated the better.

Before walking begins, a practitioner may guide the patient through pre-walking exercises to ready other pertinent muscles. If a patient’s trunk muscles were affected, causing him or her to lean to one side or to the front, therapy may start with core strengthening exercises in a sitting position.

The next step might be to work on standing until the patient feels anchored and secure. Learning to walk again involves scores of muscles and many isolated movements. Caregiver/practitioner and patient should approach the complex act of learning to stand and walk again in a safe, supported manner.

Physical activity remains a cornerstone in risk-reduction therapies for the treatment of brain injury. Regardless of how a brain injury survivor learns to walk again, one thing is certain: the survivor needs to get safely moving.

The months or years of recovery may seem overwhelming, but brain injury survivors, caregivers, and practitioners need to keep in mind that the potential for progress is always there.

Early intervention is key

By necessity, early gait intervention comes second to the other complications and concerns of a healing body.

However, literature shows that the best time for starting independent gait recovery occurs as soon as it is safe to do so, hopefully within the first few months after injury.

There is growing evidence showing the provision of early ambulation support to critically ill and injured patients result in more favorable recovery outcomes as compared to less aggressive approaches.

A recent study at Cleveland Clinic found that patients participating in early mobility routines after neurological injury recovered quicker and went home earlier than those receiving standard care.

Evidence based practice confirms that ambulation spanning the acute through long-term brain injury recovery phases using an over-ground, all-in-one standing frame and walking frame support system, such as the Gait Harness System, should be encouraged. Functional recovery progress may then be made immediately, and in the months and years to come.

Overcoming risks

Brain injury survivors (and the caregivers who help them) are often concerned about learning to walk or exercise due to loss of motor control, and related fears of falling — a fear that can lead to them being stuck in the house, and confined to bed or wheelchair. The risks of falling, experiencing a fracture, and suffering another brain injury are increased for the BI survivor.

Impairments resulting from brain injury, such as lack of energy, mood swings, verbal and visual impairment, muscle weakness, pain, contracture, spasticity and poor balance can lead to a reduced tolerance to activity and further a sedentary lifestyle.

Immobility-related complications are very common in the first year after a severely disabling brain injury. Patients who are more functionally dependent in self-care are likely to experience a greater number of complications than those who are less dependent.

To reduce risk of falls, individuals are encouraged to exercise regularly, focus on leg strength, weight bearing exercises, and improving balance. Tai Chi programs can also be helpful.

Bone mineral is lost during immobilization. Sitting for more than 8 hours a day has been shown to negatively impact health and mortality. Standing and walking again are the recommended healthier alternatives.

Neuroplasticity

Traditionally, treatment has focused on adaptation, or learning to live with the resulting impairments. However, considering incoming research and evidence based reports, many practitioners, caregivers, and clients are looking at the opportunity for recovery.

The term “neuroplasticity” or “brain plasticity” describes the brain’s ability to reorganize by forming new neural connections necessary for recovery. both physically and functionally, throughout life, due to environment. Engaging in an active standing and walking process sends messages back to the brain, until the movement is relearned.

Neuroplasticity has profound impact on recovery from brain injury because it means that with repeated training/instruction, even the damaged brain is plastic and can recover.

We are starting to realize there is more potential for recovery of the brain, and that recovery is not limited to the early months post BI. One of the biggest shifts in our understanding of brain plasticity is that it is a lifelong phenomenon.

More physical activity has been shown to improve brain functioning and improve executive function, which plays a role in reasoning and problem solving. Using MRI scans, researchers found that higher levels of physical activity also led to increased levels of brain activity while doing multiple tasks. Research is also showing that exercising regularly stalls brain shrinkage.

The right exercise, for the right duration, at the right time, can promote neurotrophic growth factors.

Over-ground therapy is more effective than robotic BWSTT

Over-ground walking is an effective means to regain greater independence of gait. The Gait Harness System provides a secure, comfortable, safe environment for the brain injured client to practice functional standing and walking again.

Body weight support treadmill training (BWSTT), which relies on total guidance of robotics, leaves little room for active effort on the part of the client, a key aspect in motor learning and functional gains.

Research shows that for most participants, BWSTT is not sufficient to induce long-term improvements in balance and balance confidence. Additionally, a recent study confirmed that body weight–supported treadmill training is no better than over-ground training for individuals with stroke/non-traumatic brain injury.

Comparing over-ground training to the robotic treadmill training suggests that it is not the length of time spent in training, but rather how an individual engages in the activity that produces the results. Or, that a greater number of step repetitions produces greater functional change in walking ability, but only when transferring the skill to a natural walking environment.

In non-traumatic brain injury survivors living in the community with marked limitations in walking, treadmill training with BWSTT was not shown to be superior in improving the functional level of walking to home administered physical therapy focused on less-intensive but progressive strength and balance training.

Studies also show that walking on a treadmill does not carry over well to over-ground walking. The active motor requirements in over-ground walking appear to be an important factor for promoting spatial symmetry in gait.

Compared to BWSTT, a recent study showed that step-length symmetry ratio improved only with the over-ground therapy gait group. Reduced step length symmetry ratio has been found to increase fall risk. Improving step length symmetry through over-ground gait training has the potential to decrease fall risk.

Improving gait symmetry through over-ground practice, in the “real world,” contributes to a goal of more “normal” walking patterns.

The Second Step GHSII encourages client-centered, supported, faster walking and more functional, natural movement. The System provides a novel, optimal gait training strategy for brain injury survivors, enabling goal-directed recovery and maintenance of walking ability.

Ready, set, walk!

Walking speed predicts the level of disability. Regaining independent ambulation, and increasing walking capacity, is a top priority for individuals recovering from brain injury.

Thus, physical rehabilitation post-brain injury should focus on improving walking function and endurance.

The Journal of Brain Injury recently reported that patients in the slow-to-recover subset of severe TBI may benefit from longer trials of rehabilitation, with functional recovery continuing to improve months or years after injury. (Grey D.S. 2000)

The best way to improve coordination, balance, and learning to stand and walk again, is by practicing regularly. Too often patients only do their exercises in physical therapy.

Some days putting in the hard work for brain injury recovery can be difficult. Recovery takes time. However, there should be gradual ambulation improvements over the first several months.

Maintaining those exercises long term, for as many years as is needed, is often needed to maintain the gains made in therapy.

With proper practitioner/caregiver support and safe therapy equipment, brain injury survivors can reduce high risks for falls, fractures, learned non-use behavior, subsequent brain injuries, and further declines in mobility.

Beginning to walk again, even long after a brain injury, has been associated with functional gains.The future for people recovering from brain injuries is more optimistic than it has ever been.

Repetition, intensity, practice: it takes willpower

Research shows that brain injury recovery is boosted by longer and more intense rehabilitation. Care and treatment for brain injury may be required across the life span. Cognitive and functional recovery after a brain injury requires intense rehabilitative therapy to help the brain repair and restructure itself.

New findings by researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine report that not only is rehabilitation vital, but that a longer, even more intense period of rehabilitation may produce even greater benefit.

Researchers found that intensive therapy, for an extended period, showed significant restructuring of the brain around the damage site. The result was a dramatic 50% recovery of function.

How do brain injury survivors move beyond the obstacles of learning to walk again? Through caregiver and practitioner support, sheer determination, and a mindset of never giving up, no matter how long it takes: repetition, intensity, and practice.

Coordination, balance, and walking exercises need to be done about five times per week, sometimes more than one time per day to get the full effect. As always — practice, practice, practice, and the survivor should hopefully see progress learning to walk again.

Studies show a daily commitment to standing and walking therapy practice (or ideally multiple therapy sessions daily) yields the best outcomes.

GHSII allows for therapy in the clinic, and in the home

Typically, the amount of walking completed by post brain injury individuals attending rehabilitation is far below that required for independent community ambulation.

Increased walking activity after discharge from rehab will improve walking function, physiological condition, psychological health, psychosocial connection, and community re-integration.

However, often the amount of walking completed by individuals with brain injuries attending rehabilitation is far below that required for independent community ambulation.

If you’ve worked with a rehab therapist, you’ve likely heard them emphasize the value of home carryover exercises in between sessions, and the importance of quality, consistent, focused practice at home once therapy is finished.

Treatment intensity and duration in hospital and skilled-nursing facilities cannot be maximized to the point required for optimal recovery, nor do these environments provide appropriate demand or context to allow efficient and effective learning or generalization of learning. Researchers have not been able to identify a ceiling for treatment intensity. More therapy is better than less.

Advances in therapy equipment, such as provided by the Gait Harness System II for Home Users, allows clients to actively participate in therapy in their homes at their convenience, empowering them to take control of standing and walking again therapy, instead of being passive consumers.

Evidence supports the impact of home-based supported standing and walking programs on range of motion and exercise activity. 60 min of standing and walking practice daily is suggested for mental function and bone mineral density. The Second Step GHSII provides a unique, safe combination of standing frame and walking frame benefits for brain injury survivors who need the extra support while learning to walk again.

Many people think after a certain number of years, they’re not going to make progress. Research shows that is simply not true. With hard work, people with TBI can continue to improve their balance for many years after injury.

Walking again enhances life quality. Every step forward is progress.

Gait Harness System product acquisition is an investment in the user’s recovery process. GHS products and accessories are therapy tools, useful for clients learning to stand and walk again, working through a broad range of user challenges. GHS products are not designed to treat or cure any issue, condition or disease. All leases, lease-to-owns, layaways, and sales are final. Clients are always advised to consult with the intended user’s doctor or health care provider regarding health-related questions, assessments, and recommendations, including addressing the user’s specific medical issues, limitations, or needs.

References

http://dana.org/Cerebrum/2012/Repairi…_Function/

Katz DI, et al. Recovery of ambulation after traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004; 85(6):865-9.

https://www.secondstepinc.com/walk-again-post-bi

https://www.secondstepinc.com/brain-injury-survivor-gallery

https://www.secondstepinc.com/resources

https://www.secondstepinc.com/why-stand-why-walk

We believe the GHSII provides greater versatility than any standing frame, walking frame, standing walker or gait trainer. Visit our to see how the System works.

Connect to our

, , , ,

and pages for more helpful, detailed information.

If you are ready to step forward and learn to walk again in a more natural way, we stand ready to help.

Contact usto request a free quote

Questions about the Second Step Gait Harness System? Call us at 877.299.STEP (7837), visit our website ator Contact us Today at

Now people can get the help they need to stand and walk again. Visit to find out more about the results oriented, clinically proven Second Step Ga

it Harness System (GHS) and NEW Gait Harness System II (GHSII).

Since 1989 the Second Step GHS has been the durable standard of excellence in commercial grade rehab standing frame and walking frame equipment.

The System provides new therapy opportunities to walk again, even for those who have not walked in years, helping people regain healthy functioning after stroke, brain injury, cerebellar degeneration, spinal cord injury, orthopedic, neurological, lower extremity amputation, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and other ambulation, gait and balance rehabilitation issues. The GHS is more than just a standing frame, walking frame, gait trainer or walker.

The GHS is used world-wide not only in outpatient and inpatient clinics, but also in the home, with both indoor and outdoor applications.

Discover how Second Step is “Helping People Walk Again” by keeping users, caregivers and practitioners safe, and simultaneously facilitating healthy, functional therapy outcomes.

Follow us on Facebook: